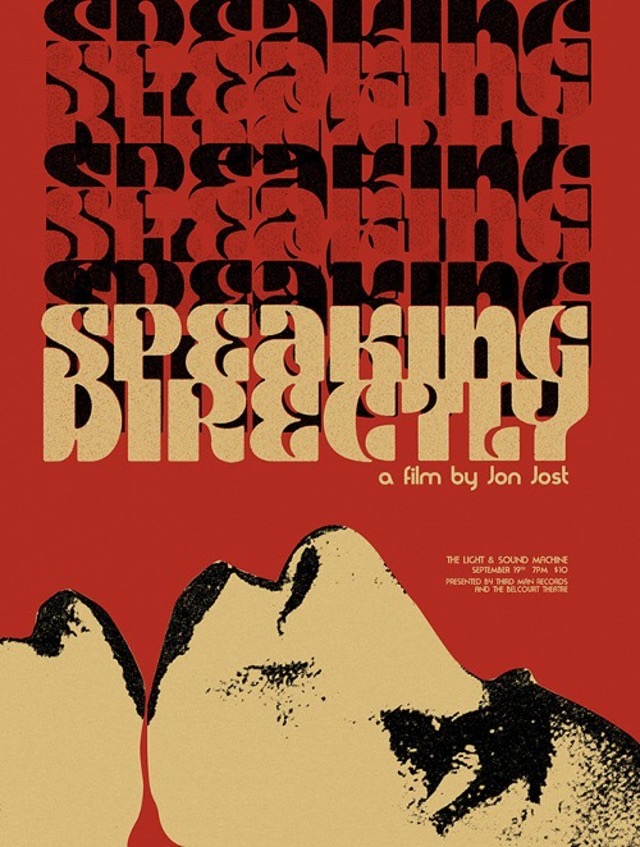

04 Mag Cinema, Arte e Natura: una (non nostalgica) conversazione con Jon Jost

Cinema, Arte e Natura: una (non nostalgica) conversazione con Jon Jost

a cura di Dafne Leda Franceschetti

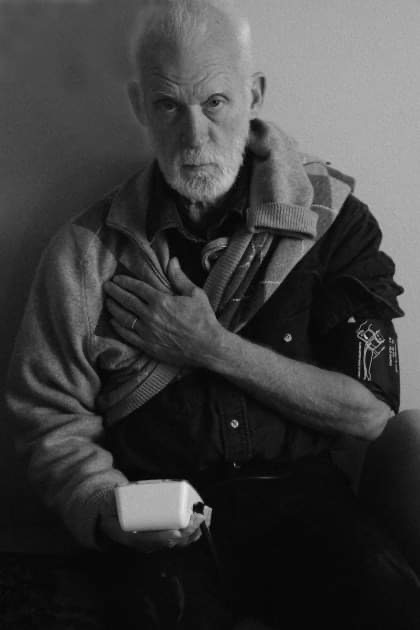

Nato a Chicago, Illinois, nel 1943, Jon Jost è un prolifico regista e fotografo americano, noto per la sua capacità di lavorare in modo indipendente, spesso improvvisando, senza copioni scritti e con budget estremamente limitati. Ha iniziato a filmare nel 1963, dopo essere stato espulso dal college; poco dopo ha anche trascorso due anni in prigione per la sua opposizione alla guerra del Vietnam.

Il suo lavoro è caratterizzato da un approccio insolito e assolutamente libero alla narrazione, una grande sensibilità per l’immagine cinematografica, uno sguardo politico e impegnato e una riflessione sul ruolo dell’arte e della natura nella nostra società capitalistica. Oggi continua a fare film, sempre sperimentando e giocando con i formati e i media.

Lo abbiamo incontrato – virtualmente, come impongono i tempi in cui viviamo – e abbiamo avuto una lunga conversazione: abbiamo parlato di arte, di paesaggio, dell’Italia (che sarà presto il set e la protagonista del suo prossimo progetto), dei giovani cineasti e del cinema d’avanguardia, se questa parola ha ancora un senso, o forse siamo tutti caduti in quello che Adorno chiamava “il paradosso dell’avanguardia”…

Vorrei iniziare con una riflessione su alcune parole chiave che ricorrono nelle sue opere, una in particolare, “Realtà”. Inoltre, l’idea di realtà è al centro del dibattito estetico e filosofico contemporaneo. Oggi, infatti, nel cinema e nella televisione i confini tra fiction e documentario, finzione e realtà sono sempre più sottili e, talvolta, quasi invisibili. Dunque, come percepisci e sperimenti la realtà o la stessa idea di realtà, che sembra essere davvero importante nella tua carriera di filmmaker (anche documentarista) e fotografo? E come si è evoluto il suo punto di vista, il suo sguardo sul mondo, durante questi anni?

Quando ero molto più giovane ed ho iniziato a fare film non posso dire che pensassi alla teoria, diciamo piuttosto che pensavo, non importa a cosa. Ho smesso da tempo di pensare e riflettere a lungo riguardo al fare film, ora semplicemente faccio, meno pensiero e più azione.

Nella mia vita ho fatto moltissimi film e di vario tipo: film-saggi, una serie di film che alcuni chiamerebbero “documentari”, eppure sono semplicemente riprese del mondo in cui mi trovo e mi sono trovato, orchestrate in qualche modo; e poi i film di finzione: eppure la gente forse non sa che anche per questi film non esistono sceneggiature scritte; vado semplicemente a cercare un posto, delle persone, un’atmosfera che desta il mio interesse; è in quel momento che potrebbe sorgere un’idea chiara di quello che voglio dire, ma non la troverete mai sulla carta, nasce l’idea e poi, semplicemente, giro il film.

Spesso, infatti, quando faccio delle proiezioni con il pubblico, mi piace fare un parallelo tra il cinema e la musica: sono un musicista jazz molto esperto e se mi si dà un tema, amo giocarci. È come se suonassi il cinema invece del jazz. Come con la musica mi viene da dire «ok, questo è il mio tema, ho tutti i miei ingredienti, i miei luoghi, i miei volti, ora cosa ci costruisco?». Ed ecco che posso iniziare a realizzare il film.

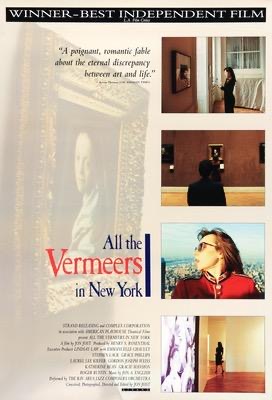

Quindi, il mio approccio è, secondo questo standard, molto sciolto, lascio molto spazio anche agli attori, eppure osservando i miei film non si direbbe, si potrebbe dire, anzi, che hanno un aspetto molto formale, in generale. Il miglior esempio per quanto dico è sicuramente All The Vermeers in New York (che ora è su Mubi Italia). Penso che quando la maggior parte delle persone lo ha visto deve aver pensato: «Oh, deve avere uno storyboard e una sceneggiatura!», ma nella realtà io non ho scritto nulla, non una parola su carta ma una moltitudine di pensieri nella mia testa. Certo sapevo vagamente cosa sarebbe stato il film, il suo soggetto– o tema, per dirla con la musica – : New York, il mondo delle gallerie d’arte, il mercato azionario e le suggestioni che fuoriescono dalle meravigliose opere di Vermeer (New York all’inizio si chiamava New Amsterdam). Questo era già tutto nella mia testa. Inoltre, il primo crollo della borsa era scoppiato a causa dei bulbi di tulipani in Olanda. Tutto questo era un po’ sullo sfondo, un filo rosso invisibile, e nient’altro. Per il resto non c’era nessuna sceneggiatura. Prendiamo ad esempio la scena iniziale con il broker da solo in un bellissimo loft a Soho: per questa scena avevo il permesso di girare nell’ appartamento per 5 soli giorni. Ero l’unico membro della troupe, ero io stesso l’operatore, senza nessuno ad aiutarmi con la fotografia e simili. Il primo giorno di riprese ho detto agli attori: «Ok, qualcuno ha qualche idea?»; nessuna risposta alla mia domanda e dunque non abbiamo girato il primo giorno. Siamo tornati il giorno dopo ed ho ripetuto la domanda «Qualcuno ha pensato qualcosa?». Silenzio. Quindi non abbiamo girato neanche il secondo giorno. Due dei miei cinque giorni a disposizione erano andati; così il terzo giorno ho detto, «Allora, qualcuno ha qualche idea?», «No». Allora ho detto: «Cominciamo dalla realtà».

La realtà però è che letteralmente non sapevamo come iniziare il film. Non a caso le prime battute pronunciate sono state queste: «dove sono le mie battute?», perché letteralmente non le avevamo. Tutto ciò che oggi vedere sulla scena accadde come per magia, poi abbiamo girato tutto il resto in due giorni. Eccola la realtà.

Quindi, quando la gente mi chiede come faccio a fare film la mia risposta è semplice: «vado in giro e seleziono “pezzi di realtà” che posso permettermi – perché non posso permettermi tutto –». Di solito, il mio modo è quello di camminare lungo le strade, cercare oggetti, persone e luoghi come tessere del puzzle sui marciapiedi, e vado avanti finché non trovo abbastanza pezzi di puzzle da poterne fare un film. E poi devo solo capire come tutti questi pezzi del puzzle s’intrecciano insieme, e dargli una forma, la forma del cinema. In sostanza raccolgo questi pezzi di realtà e li riordino per creare, laddove possibile e secondo la mia sensibilità, un qualcosa di coerente. Non mi piace pensare a loro come a delle storie: sono storie ma semplicemente non mi viene da pensare in quel modo.

È molto interessante la sua idea di cinema, il suo metodo che stabilisce un rapporto incredibilmente libero e sciolto tra immagine cinematografica e mondo reale, tra lei e le cose che la circondano. E a questo proposito mi viene da pensare a un film straordinario come The Bed you Sleep In. Come ha lavorato in quel caso? Ha usato di nuovo il suo metodo da “jazzista”? Si è trattato di totale improvvisazione?

All The Vermeers In New York era tutta improvvisazione ma, è difficile da descrivere, come dicevo, ho parlato a lungo con gli attori. Ogni tanto potevo dire cose tipo, «ho bisogno che tu dica questa battuta, a modo tuo certo, trova tu come dirla».

Ma in The Bed You Sleep In, nella scena iniziale nell’ufficio, ho detto semplicemente «Dovete andare in questo posto, la falegnameria, avete l’uso gratuito del deposito di legname, state in ufficio e poi voi, ragazzi, create un dialogo, scegliete da soli qualcosa da dire!». Anche in questo caso non c’era nulla di scritto, o magari l’hanno scritto loro ed io non ne so nulla. Altre parti di quel film, come la scena della lettera, erano un po’ più scritte, ma sempre in modo approssimativo.

Quando dico che improvviso sono serio ed ho un metodo preciso, non abbandono la gente davanti alla cinepresa intimandogli di dire qualcosa; illustro invece ciò che le cose stanno cercando di essere, ma non sono solo io a dire alle persone cosa fare, è piuttosto il film stesso a dettarci la linea, a svelarci ciò che vuole essere.

Ribadisco spesso al mio pubblico che ho una visione inusuale e personale delle riprese: non potrei realizzare film di fiction o qualcosa dove tutto è perfettamente generato a monte nella mia testa perché la mia testa non pensa così; quello che posso fare è dire: «Ok, questa realtà è intorno a me, posso usarla, raccogliere questi pezzi insieme e farne qualcosa».

Quindi, in questo continuo “gioco” con la realtà, qual è il ruolo che assegna al paesaggio? Perché, se analizziamo la sua produzione (non solo cinematografica ma anche fotografica), quello che ne viene fuori è una centralità assoluta della Natura.

Beh, non ho un punto di vista generale in merito. Ho fatto numerosi film sul paesaggio (ad esempio un film fatto da una lunga inquadratura di due ore e venti a camera fissa al Bowman Lake, nel parco glaciale del Montana).

Innanzitutto, penso sempre al luogo in cui mi trovo, a quale storia gli appartiene ed a come catturarla, e per questo sono molto attento all’ambiente: se scelgo di girare un film a Portland significa che tale film potrebbe essere girato solo a Portland. Prendiamo ad esempio The Bed You Sleep In che ho girato in Oregon – dove avevo vissuto in precedenza -. All’epoca ho esplorato il paese a lungo, cercando la città giusta; avevo anche un amico che conosceva bene lo stato e viveva lì ed allora gli ho chiesto: «Ho bisogno di una città di legname», perché all’epoca – ora non ne sono sicuro perché hanno tagliato quasi tutti gli alberi – il legname era una delle principali risorse economiche dell’Oregon. Così, volevo trovare una città ricca di falegnamerie ed il mio amico mi disse che conosceva alcuni posti interessanti e forse giusti per il film. Ma quando ci sono andato e non mi sono piaciuti; non mi aveva mostrato la città in cui ho girato. Mi ricordo infatti l’epifania: ho guidato ed appena sono arrivato in cima alla collina ho visto questa cittadina ed ho detto «È quella!», perché non era pianeggiante, era collinare, e c’era qualcosa di bello che potevo ottenere da quella vista che offriva e dal poter guardare le strade ed avere una bella prospettiva. Era assolutamente il posto giusto, così ho iniziato a fare ricerche sul territorio. Improvvisamente ho scoperto che nelle falegnamerie della città l’attività principale era la produzione di cellulosa per la carta, ma ad affiancarla c’era un’altra attività che utilizzava pezzi di legno molto grandi che richiedevano alberi millenari – quel legno può essere usato in ambienti industriali come le miniere o qualcosa dove si richiede legname di grandi dimensioni – e mi hanno dato il permesso di girare lì, così ha iniziato a prender forma quello che sarebbe stato il film.

Alla fine potrei dire che almeno la metà di questo film, non solamente i paesaggi, è un modo di estrapolare dalla narrazione l’ambiente stesso in cui la narrazione avviene: come quella lunga inquadratura all’interno del caffè che narrativamente non ha una vera funzione perché la sua funzione era ed è quella di restituire in un’inquadratura il senso della città; e come questa, altre scene ed inquadrature che normalmente annoiano a morte gli spettatori.

Quindi, la mia idea di paesaggio, dei paesaggi urbani, delle città, dei villaggi, è tutta dovuta ad un senso di obbligo morale, ad una necessità di dire che questa storia accade in un particolare mondo e di rivelare che un particolare ambiente dà vita ad una determinata storia. Ecco perché i miei film sono pieni di inquadrature in cui l’ambiente è protagonista senza alcuna narrazione, senza che ci sia un personaggio nell’inquadratura, senza un legame diretto con la storia.

E risultano così spesso come paesaggi astratti e misteriosi, Paysages in the Mist… Ho citato Angelopoulos di proposito perché alcuni critici hanno avanzato un parallelo tra i suoi «paesaggi drammatici», la «natura astratta» che lei mostra nei suoi film ed il cinema del regista greco, e anche, forse, quello di Herzog. Con Herzog, inoltre, lei condivide uno spirito da viaggiatore”…

Ho visto solo due film di Angelopoulos, i primi; invece devo dire ahimè che Herzog non mi piace: il mio problema con lui è che risulta sempre il protagonista di tutti i suoi film. Fa spesso una cosa che proprio non mi piace, cioè l’autocelebrazione.

E nella sua particolare attenzione all’ambiente ed alle storie che ne scaturiscono, perché ha scelto l’Italia per i suoi prossimi progetti?

Ho girato la prima volta in Italia molto tempo fa il film Uno a me, uno a te ed uno a Raffaele, ed ho avuto non pochi problemi lì. Perché a tutti i critici di allora piaceva molto quando davo del filo da torcere all’America, ma non gli è piaciuto affatto quando ho fatto a loro quello che avevo fatto all’America: fondamentalmente, stavo dicendo che tutti sono corrotti. So con certezza che non avrebbero avuto problemi se avessi mostrato una situazione alla “mani pulite”, dove solo i grandi capi sono corrotti, ma la corruzione generale e diffusa che hanno visto nel mio film non gli è piaciuta per niente.

Comunque, anche se considero l’Italia un paese pieno di contraddizioni e intrinsecamente malinconico, mi piacerebbe tornare in Italia e passarci il resto della mia vita.

In Sicilia, dunque?

Beh, potrei vivere ovunque, mi piacciono molti posti, ma amo Palermo perché è una città molto viva e vivace ed è ancora molto popolare, un posto vero, ed è una cosa rara.

Per quanto riguarda i miei prossimi progetti, ammesso che continui a fare film, al momento ho solo una vaga idea: sarà qualcosa a Palermo. Questa città è piena di arte meravigliosa e di gemme nascoste, per esempio nel quartiere di Ballarò c’è una piccola chiesa che da fuori sembra stia per crollare, ma da dentro è incredibile. Insomma, come ho detto, al momento è tutto ancora in embrione ma sono in contatto con un produttore a Roma, Andrea De Liberato, che ha prodotto anche film di Greenaway. Quando l’ho conosciuto era abbastanza giovane, era alla fine degli anni ’90– quando vivevo lì – ed ora sto cercando di convincerlo che dovrebbe lasciarmi fare un film a modo mio. Gli ho detto: «se puoi darmi 70.000 euro posso farne un film che a chiunque altro costerebbe 2 milioni, ma devi lasciarmi lavorare a modo mio: non voglio una troupe, ci sono solo io. Non ho nemmeno bisogno di un fonico, ci sono io e forse, qualche volta e visto che sono vecchio, qualcuno che mi aiuti come operatore, così, una volta ogni tanto, potrei fare qualcosa di più elaborato. Ad ogni modo in generale, ciò di cui ho bisogno è il tempo – un anno, almeno – per girare con la mia calma ed alla mia maniera, ed abbastanza soldi da parte per pagare gli attori quando mi servono, e potrebbero anche servirmi per sole due settimane in un anno…insomma, non sono sempre riuscito a convincerli!

Il suo modo di filmare è un modello per un’intera generazione di giovani artisti sperimentali, anche in Italia, per esempio Ilaria Pezone, artista e regista italiana, ha detto durante un’intervista che i suoi film sono stati per lei una vera scoperta e un’importante fonte di ispirazione. Lo stesso Jean-Luc Godard, le “grand maître du cinéma“, ha commentato i suoi film anni fa, dicendo, cito, che «A differenza di quasi tutti i registi americani, lei non sei un traditore dei film. Lei li fa muovere» …

Sì certamente, conosco bene Ilaria, quanto a Godard quella citazione veniva da un giornale… La detesto. Era intorno al 1974, o qualcosa di simile, prima che facessi il mio lungometraggio; ho fatto dieci anni di cortometraggi e lui ha visto uno dei miei corti. Vorrei che non l’avesse mai detto, perché questo commento volteggia sulla mia testa come un avvoltoio. Ma c’è una cosa che la gente dovrebbe sapere di Jean-Luc: che è molto bravo a fare frasi brevi e citazioniste come «Il cinema è verità 24 volte al secondo». Bello, peccato che non sia vero!

Ed ha un migliaio di queste frasi perfette pronte a divenire citazioni celebri che però non stanno in piedi. Appaiono carine ma non reggono.

D’altronde gli aforismi sono tutti un po’ così, puro effetto e poca sostanza…

Sì, e soprattutto i più famosi sono così!

Lasciando da parte Godard e le sue provocazioni, lei resta comunque un modello imprescindibile ed intere generazioni di cineasti di tutto il mondo hanno seguito e seguono la tua produzione sfaccettata, la sua sensibilità per cinema, arte e fotografia – ed anche il MoMa ed altre fondazioni le hanno dedicato importanti retrospettive negli anni -.

Ed in questi anni lei ha sempre mostrato un’attenzione particolare per l’aspetto materico del cinema, lavorando in pellicola e giocando con i differenti formati e le nuove tecnologie disponibili. Poi hai definitivamente abbandonato il mondo di celluloide. Perché? Sente la nostalgia, come accade a molti suoi colleghi registi, di questo “universo perduto”?

Non ho assolutamente nessun sentimento nostalgico! Ho fatto film in pellicola per quasi 40 anni, ma, se non hai soldi, come me, – ed io non ho mai avuto soldi – allora devi solo andare avanti, perché lavorare in pellicola comporta una serie di regole e imposizioni, detta il ritmo del lavoro; per questo da un certo punto di vista sono grato di aver lavorato in pellicola ai miei esordi, perché mi ha fornito una sorta di disciplina. Ho passato dieci anni a fare cortometraggi (beh, non ho passato davvero dieci anni perché due li ho passati in prigione, dove non potevo esattamente fare film!) ed è stata un’ottima scuola di rigore da cui ho imparato molto; ma d’altra parte si è anche rivelata una cosa negativa perché davvero troppo costosa.

Per tornare a quanto ho detto all’inizio, sebbene il mio metodo si è andato orientando verso l’improvvisazione, il mio primo film lungo, Angel City, era completamente sceneggiato, perché visto che era in pellicola all’epoca pensai che lavorare con un testo scritto fosse il modo meno costoso: l’assunto era che se sapevo cosa volevo fare e lo facevo bene allora non dovevo girare molto – e spendere molto –. È costato seimila dollari; subito dopo ho fatto Last Chants for a Slow Dance che è più lungo ed è costato tremila dollari ed era più o meno completamente improvvisato, così ho cambiato idea e ho scelto di continuare con l’improvvisazione.

Inoltre la pellicola è molto più complicata da lavorare e già attorno al 1996 iniziai a sentire molto le limitazioni del mezzo: c’erano cose che volevo fare ma non potevo, e quando è arrivato il digitale, non appena ho preso la telecamera in mano mi sono detto «Ok, non userò mai più la pellicola».

Tra le altre cose mi piaceva esteticamente, perché ci si potevano fare cose che non assomigliavano affatto a film.

Per undici anni ho lavorato con il digitale (finché nel 2008 non sono passato all’HD) ed ho usato le sue qualità; poi è arrivato l’HD che a sua volta era un’altra cosa, aveva un aspetto completamente diverso. Quando poi ho fatto quest’ulteriore evoluzione mi sono nuovamente detto «ok, questa è la sua qualità, e ho intenzione di sfruttarla».

Quindi sì, sono molto attento al mezzo ed ai linguaggi a disposizione, ma non ho pensieri romantici su di esso. So che molte persone più giovani lo fanno ed a volte fanno cose che mi irritano davvero, come alcuni registi più giovani che millantano una finta nostalgia davvero fastidiosa: com’è possibile la nostalgia senza aver avuto quell’esperienza?

Parlando di musica, Simon Reynolds e Mark Fisher hanno chiamato questo fenomeno – perfettamente applicabile al suo discorso – «Retromania», una sorta di ossessione romantica per un passato superato o mai vissuto.

Sì, lo so, e in un certo senso capisco psicologicamente perché la gente ce l’abbia, però sono stato a moltissimi festival di cinema “d’avanguardia”, come giurato e cose simili, e mi si è generato un odio profondo davanti a tutti questi giovani che abusano di questa estetica “nostalgica”: graffi, polvere, patine che imitano la pellicola e così via… facile quando ci sono programmi informatici che fanno tutto il lavoro sporco al tuo posto….

Però si possono usare anche gli archivi.

Beh, sì, la gente spesso fa anche una specie di “film–collage” usando di tutto.

Ma la parte che mi irrita di più è che quando vai a uno di questi festival d’avanguardia vedi solo imitazioni di cose fatte quaranta e cinquant’anni fa e non c’è niente di “avant” in questo. Io li chiamo film “derrière-garde“. Vorrei vedere giovani che fanno qualcosa che non ho mai visto prima, piuttosto che una cosa completamente rigurgitata che ho già visto cinquant’anni fa. Non voglio vedere un remake di qualcosa che ha cinquant’anni, voglio vedere qualcosa di nuovo, qualcosa che mi stupisca!

C’è un giovane regista inglese, Scott Barley, che ha fatto un film meraviglioso che si chiama Sleep Has Her House, un lungo film senza narrazione, immagini stupefacenti, tutto molto oscuro e tenebroso, ma un film molto bello. Voglio vedere più film come quelli di Scott, dove posso dire onestamente a me stesso «non ho mai visto un film così prima», e solitamente non mi impressiono anche se è qualcosa che non ho mai visto prima ma non è buono, ma nel caso di Sleep Has Her House è stato così: Non ho mai visto niente del genere ed era più che buono, era un film davvero bello e stupefacente.

Parlando di altri registi innovativi ce n’è un altro che è molto interessante per me e che ci riporta alla tua domanda sui media e sul lavoro con i linguaggi cinematografici: si tratta di un irlandese che si chiama Donal Foreman che ha fatto un film semi-biografico su suo padre e su di lui. Suo padre era un regista irlandese americano che sposò una donna irlandese e visse gran parte della vita a Parigi ma era ancora ossessionato dall’IRA e dalla guerra civile in corso in Irlanda. Questo film è molto interessante e lo sono anche le clip d’archivio del lavoro di suo padre. Poi è diventato anche lui un regista e ha iniziato in VHS, poi ha continuato ad esplorare i mezzi espressivi per poi finire, come me, in HD.

È chiaro che lei non è assolutamente un nostalgico, ma ha detto a più riprese che vuole filmare «alla sua maniera», con il suo metodo libero ed indipendente ed i suoi lavori hanno via via preso le distanze dal cinema commerciale contemporaneo. C’è solo una spiegazione economica dietro o anche una politica?

Beh, è tutto un insieme di cose, certamente c’è una spiegazione economica, ma ciò che economico è politico, no? Prima di tutto perché ad esempio, se ho una troupe di dieci persone serviranno molti soldi e tutti quei soldi esigono un certo tipo di film, il tipo di film che mi farà riavere quei soldi: tutto questo è politico.

Poi c’è un secondo livello: io non ho un set, non amo che le persone osservino e siano d’intralcio, voglio solo gli attori necessari alle riprese oltre a me. Così tutto diventa molto intimo e si crea una bella atmosfera. Non appena si aggiunge un cameraman, un fonico o una qualsiasi altra persona, i tempi di lavorazione si moltiplicano.

In The Bed you Sleep In e All The Vermeers, ognuna di quelle scene è stata girata in due o tre ore, se avessi avuto una troupe al completo ci sarebbero voluti almeno due o tre giorni, o forse settimane. Dunque la mia scelta è dovuta al fatto che, almeno per come sono solito lavorare io, farlo con una troupe è solo d’intralcio per la maggior parte del tempo, e poi lavorare alla mia maniera mi permette di fare i film con 500 dollari. The Bed you Sleep In è costato 500 dollari ma è stato fatto in 35 mm. Per quei due film avevo un assistente alla macchina da presa ed un fonico e null’altro.

Per tornare alla tua domanda originale sui linguaggi espressivi ed i formati, mi ricordo che quando il digitale uscì per la prima volta c’erano moltissime persone che cercavano di capire come farlo apparire simile alla pellicola: la loro idea di “look cinematografico” era che la maggior parte dei film di Hollywood o i film su larga scala erano girati in 35 mm, quindi cercavano di far sembrare il digitale come quello, anche se maneggiare il digitale a ben guardare è più simile a lavorare con una telecamera 8 mm, dove hai una profondità di fuoco piuttosto profonda. Quindi, stavano cercando di capire come far assomigliare una pellicola in 8 mm ad una pellicola in 35 mm, sottintendendo dunque che il 35 mm fosse migliore; quindi si continuavano a torturare: «Come faccio a dare a un’opera un look da film hollywoodiano usando lenti diverse?».

Ricordo che dicevo loro: «Perché volete far assomigliare un acquerello a un olio? Perché non accettate semplicemente che l’acquerello è bello così com’è, ed anzi è bello soprattutto se trattato per quello che è? Quindi non cercate di farlo essere qualcosa che non è!».

Per esempio, c’è un altro regista Leighton Pierce – i cui film sono visibili su Vimeo – che è passato dalla pellicola al digitale nello stesso periodo in cui l’ho fatto io, e condivide con me lo stesso principio: «non cercare di far sembrare il digitale una pellicola»; ed era un regista sperimentale esperto, come me. Questa è la nostra idea: si tratta di un altro mezzo, con una qualità propria e dobbiamo usarlo per quello che è.

Cinema, Art, Nature: a (no nostalgic) conversation with Jon Jost

(VO)

a cura di Dafne Franceschetti

Born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1943, Jon Jost is a prolific American filmmaker and photographer, known for his ability to work in an independent way, often improvising, without scripts and able to work with extremely limited budgets. He started filming in 1963, after he was expelled from college; he also spent two years in prison for his opposition to Vietnam war.

His work is characterized by an unusual approach to narrative, a huge attention for the cinematic image, a political and engaged gaze and a reflection on the role of Art and Nature in our capitalistic society. Nowadays, he continues making movies, always experimenting and playing with formats and media. We met him – virtually, as the times in which we’re living impose – and we had a long conversation: we spoke about art, landscape, about Italy (that it’s going to be soon the set and the protagonist of his next project) and about young filmmakers and avant-garde cinema, if this word still have any sense, or we’ve all fallen in what Adorno used to call «the avant-garde’s paradox»…

I would like to start with a reflection around some keywords recurring in your works, in particular Reality. Furthermore, the idea of reality it’s at the center of contemporary aesthetic and philosophical debate. Nowadays, in fact, in cinema and television the boundaries between fiction and documentaries, fiction and reality are more and more thin and, sometimes, almost invisible. So, how do you feel and experiment reality or the same idea of reality, that it seems to be really important in your filmmaker and photographer career? And, how your point of view, your gaze on the world has evolved during these years?

When I was much younger, when I started making films maybe I can’t say I thought about theory, let’s just say, I thought, whatever I thought about. I long ago quit thinking, regarding making movies, now I just make movies.

In my life I made essay films, I made a number of films that some people would call documentaries, I mean, they’re just shots of the world I’m in, orchestrated in some way. And then the fiction films: people maybe don’t know that I don’t write scripts, I just go, go find a place, some people, an atmosphere; and then I might have a modestly clear idea of what I want to say but it’s not on paper and then I just shoot the film.

Often, when I’m doing public screenings, I like making a parallel between cinema and music: I’m a very experienced jazz musician and if you gave me a theme, I really love to play with it, I play cinema instead of jazz. Instead of music I’m just saying «ok, this is my theme, I have my ingredients and what shall we make it about? » And then it just gets made.

So, my approach is, by that standard, very loose, although if you look at my films, they have a very formal look, in general. The best example is All The Vermeers in New York (that is now on Mubi Italy): I think that when most people saw it they must have thought: «Oh, it must have a storyboard and a script! », but actually I have nothing, not a word on paper but a lot of thoughts in my head. But I knew vaguely what the film was going to be, the subject: New York, the art galleries world, the stock market, the reflections that at the time Vermeer painted (New York at the beginning was called New Amsterdam); and I knew all; furthermore, the first stock market bubble had burst was in tulip bulbs in Holland. So that was sort of away in the background but it was all there, but otherwise there was no script at all. To give an example, let’s take the opening scene with the stock broker who is lonely in this beautiful loft in Soho: in this scene I was allowed to film in this apartment for 5 days; so, I went in, and I’m my own crew: I shoot the camera, I don’t have anybody doing lights or any stuff like that. The first day we started the film and I said, «Ok, does anybody have any ideas? », «No»; we didn’t shoot the first day. We went back the next day and «anybody thought anything? », «No». So, we didn’t shoot either the second day. And two of my five days were gone; as I just said I only had five days to shoot in this place and we wasted two days, so the third day I said, «Well, does anybody have any idea? », «Nope». So, I said, «let’s start with reality».

Reality is that we didn’t know how to begin the film. In fact, the first spoken lines were these: «where are my lines», because we literally did not have them. In the scene everything just happens like magic and we shot all the rest in two days.

So, the thing is that when people ask me «How do you make movies? » I say «Well, I go around and I pick pieces of reality that I can afford – cause I can’t afford anything -. Usually, my way is to go along the streets and I’ll find the jigsaw puzzle pieces on the sidewalks, and I go along until I find enough jigsaw pieces until I can make a movie out of it. And then I just have to figure out how do all these jigsaw pieces go together, and I have to put all these material pieces together and give them the shape of a movie.

I take pieces of reality and I suddenly rearrange them, to make a coherent something. I don’t like to think at them as stories: they are stories but I don’t think that way.

It’s really interesting your idea of cinema, your method that establishes an incredibly loose and free relationship between cinematic image and the real world, the things around you. And about this, I’m thinking about an extraordinary film as The Bed you Sleep In. How did you work in that case? Did you use again your “jazz-player” method? It was all improvisation?

All The Vermeers In New York was all improvisation but, it’s hard to describe, I talked with the actors a lot about “things”. I might once in a while say «I need you to say this line, your way, and you figure out how to say it».

But in The Bed You Sleep In, in the opening scene in the office, I just said «You have to go to this place, the lumber, you have free use of the lumber yard and just hang around in the office and then you, guys, create a dialogue, choose something to say! ». So, this was never put on paper, at least I didn’t put anything of this on paper, maybe they did! And some parts of that film, as the scene with the letter, were more or less written, butt always in a loosely way. When I say I improvise I’m very engaged, I don’t throw people in front the camera and say «Say something! ». I talk instead about what the things are trying to be, it’s not just me telling people what to do, it’s more like: «this is the film and this is what he wants». So, I often tell people that I don’t have a usual sense of filming: I could not make fantasy films or something where I generated all the stuff in my head, because my head just doesn’t think like that; all I can do is to say, «Ok, this reality is around me, I can use it and collect these pieces together and make something».

So, in this continue “game” with reality, which is the role of landscape? Because, if we analyze your production (not only cinematographic but also the photographic one), what comes of it it’s an absolutely centrality of Nature.

Well, I don’t have a general point of view, I made a handful of landscape’s films (as a long shot, two hours and twenty minutes steady-camera shots at Bowan Lake, in the glacial park in Montana).

I always think about the place I’m in, what story belongs there, and how to capture it, so I’m very attentive to the environment: if I shoot a film in Portland it means that it could only be shot in Portland. As example for The Bed You Sleep In, I drove around in Oregon – I lived in Oregon before – looking for the right town and I had a friend who knows Oregon and lives there I said to him, «I need a lumber town », because at that time – I’m not certain now because they cut off mostly all the trees – lumber was one of the major industries of Oregon. So, I wanted to find a lumber town and my friend told me that he knew some interesting and maybe right places. But I went there and I didn’t like them and then he didn’t tell me about the town I shot in and I remember driving and soon as I went on the top of the hill and I saw this town and I said «That’s it! », because it wasn’t flat, it was hilly – and there was something I could get about the visual and being able to look up at the streets and have a nice prospective; so I decided that it would be the place and I began to research there. Suddenly I found out that the lumber places – that in Italy you call “falegnameria” –, the major business of the town was making pulp for paper, but at the side there was this older thing that specialized in very large pieces of wood that required old trees – that wood can be used in industrial settings like mining or something where they need a big big piece of wood – and I found that and they gave me the permission to shoot there, so that started to determine what the film would be.

And along the way, I would say half of that film, not necessarily landscapes or stuff, but half of the film is in some way sketching outside of the narrative the environment in which the narrative happens, like that long shot inside the cafe by the counters and the people, narratively, that didn’t really have a real function, its function was to give in one shot a sense of the town, and then all the other shots, the shots that many people look and say «This is boring! ».

So, the idea of landscapes, townscapes, cityscapes, is all because I feel a sense of moral obligation to say that this story happens in this particular world and this particular environment gives birth to this story. That’s why my films are full of shots where the place was without the narrative, without a character being in the shot, without a direct linkage to the minimal story.

Like abstract and mysterious landscapes, paysages in the mist…I citated Angelopoulos on purpose because some critics made a parallel between your «dramatic landscapes», the «abstract nature» that you show in your films and the Greek director’s cinema, and also, maybe, Herzog’s one. With Herzog, moreover, you share a “traveler spirit”.

I’ve only seen two Angelopoulos’s films, the earlier ones, but instead I don’t like Herzog: my problem with him is that he is the star of all his films. He does something that I really don’t like, which is self-mythologizing.

And in your particular attention to the environment linked to the stories, why did you choose Italy for your next projects?

I shot the first time in Italy long time ago the film Uno a me, uno a te ed uno a Raffaele, and I had some troubles with it in Italy. Because all the critics back then liked it when I gave America a hard time, but they didn’t like it when I did to them what I did to America. Basically, I was saying that everybody is corrupted. I know that they wouldn’t have problems if I had showed a “mani pulite” situation, where only the big bosses are corrupted, but they didn’t like at all the general and spread corruption they’ve seen in the movie.

However, even if I consider Italy a country full of contradictions and intrinsically melancholic, I would love to go back in Italy and spend there the rest of my life.

In Sicily, then?

Well, I could live elsewhere, I like a lot of places, but I love Palermo because is a very lively and vivid city; it’s still very popular, a real place.

And about my next projects, assuming that I continue to make films, which I don’t film under any pressure, I have a vague idea: it will be something in Palermo. This city is full of fantastical art and hidden gems, for example in Ballarò there’s a church in the middle of the neighborhood, that from the outside looks like it’s about to fall down, but from the inside it’s amazing.

As I said, at the moment I just have a vague idea of my next work.

I was talking to a producer in Rome, Andrea De Liberato, who produced also Greenaway films. When I met him, he was quite young, it was in the late 90s, when I was living there, and now I’m trying to talk to him. I assume that Covid has done what has done everywhere else and sort of thrown anything into another something or other, and movie productions as well, so I’m trying to convince Andrea that he should let me make a movie my way. I say to him: «if you can give me 70,000 euro I can make you a film that anybody else will cost you 2 millions, but you have to let me work my way: I don’t want a crew, it’s just me. I don’t even need a sound-person, I want me and maybe sometimes and since I’m old someone who helps me carry the camera and, once in a while, I might do something a little more elaborate. In general, what I need is time –a year, at least – to shoot it my way, and enough money on the side to pay actors for when I want them: what I need, so to say, is «I need you for a year, but I can’t tell you which day and probably I only need you for ten days out of the year»…so, sometimes I have not convinced them!

Your way of filming is a model for an entire generation of young experimental artists, also in Italy, for example Ilaria Pezone, an Italian artist and filmmaker, said during an interview that your films were for her a real discovery and an important source of inspiration.

Jean-Luc Godard himself, le «grand maître du cinéma», commented your films years ago, saying, I quote, that «Unlike almost all American directors, you are not a traitor to the movies. You make them move»…

Yes, I know Ilaria! Speaking instead about Godard, that quote came from a newspaper…I kind of don’t like it. It was around 1974, or something similar, before I made a feature, I did make ten years of short films and he saw one of my shorts. I kind of wish he had never said that, because this comment sort of follows me like an albatross. And, you know, if people knew the reality which is: one thing about Jean-Luc is that he is very good in making short little quotable sentences as «Cinema is truth 24 times a second». Well, no it’s not!

And he has a mile of these kind of easily very clever quotable things that don’t hold up to analysis. They sound cute but they don’t hold up.

Yes, aphorisms are often like that: big effect and little substance, a rhetorical game. They’re just made to be remembered…

Yes, and especially the most famous are like that!

Leaving aside Godard and his provocations, you’re still considered an important model and many generations of filmmakers spread around the world have followed your multifaceted production and your sensibility for cinema, art and photography, and the prestigious MoMa Museum, between many foundations, dedicated to you an important retrospective years ago. In past times you always showed a particular attention to the material aspect of cinema, working in film and playing with different formats; then you definitely abandoned celluloid world. Why? Do you ever miss, as some of your cinematographer colleagues do, this “lost world”?

I have absolutely no nostalgic romance about celluloid! I did celluloid films for almost 40 years, but, if you haven’t got any money, like me, – I never had money – then you just have to move on, because you know, working in celluloid dictates what you can do, and on one level I’m thankful that I had worked in celluloid when I began, because it provided me a sort of discipline.

I did spend ten years making short films (well, I didn’t really spend ten years because I spent two of them in prison, where I couldn’t make films!) and it was a good discipline and I learnt a lot, but it also turned out to be a bad thing, because when I was working in films if I began to take a shot amd push the button, there was already money going by.

Despite the fact that I did end up improvising, my first long film, Angel City, was fully scripted, because I thought it was the least expensive way to work: if I knew what I wanted to do and I did it right then I didn’t have to shoot a lot. It costed six thousand dollars, right after I made Last Chants for a Slow Dance which is longer and costed three thousand dollars and was more or less completely improvised, so that changed my mind and I chose to go with improvising.

But film is much clumsier to work with – you can do a ten minute long shot in 16 mm -, and around 1996 I was feeling very much the limitations of film: there were things I wanted to do but I couldn’t, and when DV came along (I got it very early in 1996) after having the camera in my hands for like 30 seconds I was like «Ok, I’m never going to use film again».

Among other things I liked it aesthetically: I liked the way it looked because you could do things that didn’t look at all like movies, and I didn’t want to look like movies.

When I switched (from ’97 to 2008, when I got an HD camera) for eleven years I worked in digital video and I used its qualities – the things that camera can do, that movie cameras can’t -, and HD then was another thing, had a completely different look; and when I switched to it I said «ok, this is its quality, and I am going to exploit it».

So yeah, I am very attentive to the medium at hand, but I have no romantic thoughts about it; I know a lot of younger people do and sometimes they do things that really irritate me, like some younger filmmakers because of that fake nostalgia, because they don’t have that experience.

Speaking about music, Simon Reynolds and Mark Fisher used to call this phenomenon “Retro-mania”, a sort of romantic obsession for a past that we – in particular younger people- never lived.

Yes, I know and I sort of understand psychologically why people have it but then I have been to a handful of avant-garde film festivals, as part of the jury and things like that, and I really hate it when these young people abuse this “nostalgic” aesthetic: scratches, dust, etcetera…when you have computer programs that will put that up for you: you shoot in video and then you put the bad parts of film into your video.

But we can use archives, too, and this is a different thing…

Well, yeah people also make sort of “collage” films using everything.

But the part that really buzz me is when you go to an avant-garde festival and you see all these things that were done fifty or a hundred years ago: there is nothing “avant” about that.

I call them “derrière-garde” films, and I would like to see young people making something I have never seen before, rather than a completely regurgitated thing that I saw fifty years ago: I don’t want to see a remake of something that is fifty years old, I want to see something new!

There is a young English filmmaker Scott Barley that made a wonderful film called Sleep Has Her House, a long movie with no narrative, stunning imagery but all very dark and obscure but a very beautiful film.

I want to see more films like Scott’s, where I can honestly tell myself «I never saw a film like that before», and I am not impressed if it is something I have never seen before but it is not good; in the case of Sleep Has Her House it was like that: I never saw anything like that and it was more than good, it was a really beautiful stunning film.

Speaking of other filmmakers there is another one that is very interesting for me: (speaking about the media) an Irish man called Donal Foreman that made a film which was basically half biographical about his father and him: his father was an Irish American filmmaker that married and Irish woman and need up living in Paris for most of his life, but still he was obsessed with the RIA and the civil war troubling in Ireland.

This film is very interesting and so are the clips of his father’s work; then he became a filmmaker too and he started out in VHS, then went to this and that and ended up in HD, and these are all about how the politic changes, his views and his father’s ones were very different, the mediums, etcetera…it is a fascinating film.

He takes like five or six threads and he wheels them together in this very, very dense way of showing things.

So, you are absolutely not a nostalgic, but you said several times «I would like to film my way», and your way it’s really independent and loose, and your works have more and more distanced themselves from commercial modern cinema. There is just an economic explanation besides, or there is also a political one?

Well, it is a whole mess of things: while it is economic, but economic is politic, isn’t it?

So, if I have a crew of ten people and all that kind of money is going to be spent, then I have to make a certain kind of film, the kind of film that will get that money back (says whoever) which is a very big political “thing”, so that’s one level.

Another level is – in my life I often got asked «can I come to your set? », and I go like «First of all I don’t have a set, I have a place I’m shooting at», second, anybody who is there and doesn’t need to be there is just getting in the way, I don’t want other people just observing, even if they said they will be quiet, I know actors will go and talk with them; I don’t want anybody interfering, and my ideal situation is: the actors I need in the scene and me, that’s it. Then it becomes a very intimate thing: it is my relationship with the actors. As soon as you need a cameraman, a sound person, or any of those other people, it takes ten times longer with all those other people.

In The Bed you Sleep in and All The Vermeers, anyone of those scenes were shot in two or three hours; if you had a crew you would be talking about two or three days or maybe weeks.

My choice to work the way I work is because, at least for the way I do, working with a crew is just getting in the way for the most part and then working the way I do allows me to make a feature for 500 dollars.

The Bed you Sleep in costed 500 dollars but they were made 35 mm. For those two films I had a camera assistant and a sound person and that was it.

Frame up is the 35 mm film I made just after The Bed you Sleep in and me and a young woman who had done some film as a 16 mm camera assistant: she and I were the crew for a 35 mm film!

To go back about your original question about the medium you are working in, I remember when DV first came out and there were all these people who tried to figure how to make it to look the way film looked: their concept of the film look was most Hollywood movies or big scale movies were shot in 35 mm, the lenses have less depth of field (that’s why you have a whole aesthetic built around shots out of focus), so they were trying to make DV look like that, and DV is more like working with a 8 mm camera where you have a pretty deep depth of focus. So, they were trying to figure how to make an 8 mm film look like a 35 mm film, and the implicit thing in that is to assume that 35 mm is better – that’s way 35mm is what I used to looking up when I go to see commercial cinema – and I want my little no commercial cinema thing to look like, so they will torture themselves: «How do I make look like a Hollywood movie using different lenses? ». They don’t understand that the optics and the lenses are different.

I remember I would say to them «Why do you want to make a watercolor look like an oil? Why don’t you accept that watercolor is just beautiful the way it is, it’s just nice as it is, especially if treated as what it is. So don’t try to make it be something that it isn’t! ».

For example, there’s another filmmaker Leighton Pierce – you can find his films on Vimeo – who switched from film to DV at the same time I did, and he kind of have the same idea: «don’t try to make the digital look like film», and he was an experimental experienced filmmaker, like I was. We share this idea: this is another medium, with its own quality, we have to use it for what it is.

The curious thing is that, despite the differences, we did arrive at some aesthetic similarity each other: we used them in a very different way but the actual thing was very similar.

No Comments